DOCENT PICK

Liquid Nights

23/09/2024

Following institutional research on the work of pioneering women artists addressing the concept of materiality, Docent is pleased to present a curated selection of works that explore mediums and forms through fluid expression, with a particular focus on their liquid qualities.

The state of the matter

In Contingent (1969), Eva Hesse confronts the fragility and transience of material through an interplay of latex, fiberglass, and cheesecloth. These hanging, semi-translucent panels seem to defy solidity, evoking the delicate nature of human existence. Each panel, suspended in time, offers a reflection on impermanence—suggesting that even the most tangible forms are subject to decay, movement, and transformation.

Similarly, in the work of contemporary artist Lotus L. Kang, we find an intimate dialogue with the mutable qualities of matter, exploring the boundaries between solid and liquid, the organic and the industrial. Kang’s manipulation of materials—often softened, melted, or stretched to their limits—echoes Hesse’s investigations into the physicality and vulnerability of form. Both artists reveal the latent fluidity within structures, challenging our understanding of permanence and stasis.

Lotus L. Kang’s exploration of fluidity in material echoes Lynda Benglis’s bold use of poured latex and polyurethane in Untitled (1970), where both artists embrace the unpredictable, transformative nature of their mediums. Benglis captures raw energy through the dynamic, frozen motion of liquid forms, while Kang pushes material to its boundaries, reflecting a shared fascination with the tension between control and surrender. Both artists challenge traditional sculpture by turning fluidity into a core concept, revealing the beauty and power of material in constant transformation.

Ephemeral Impressions

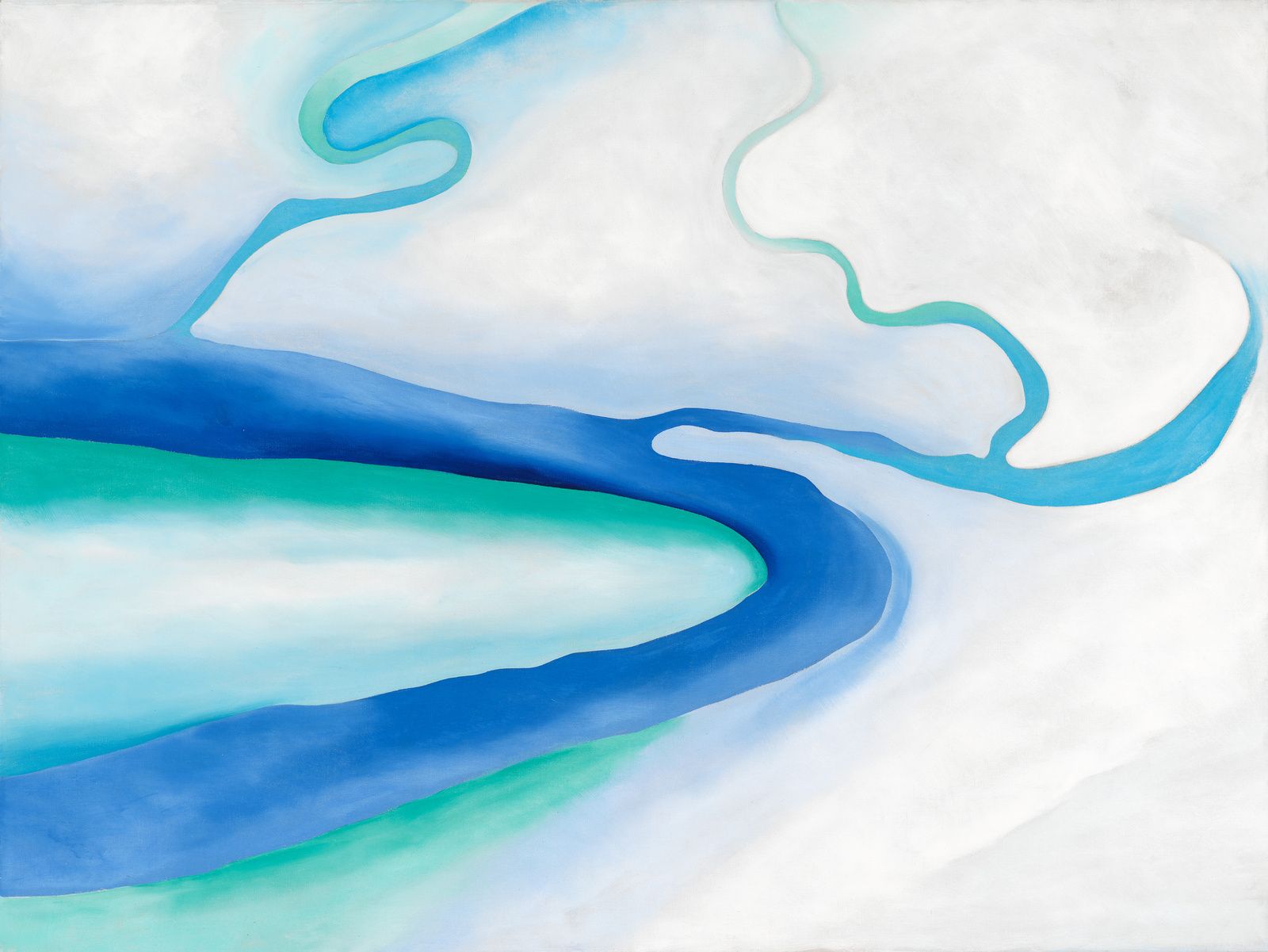

Georgia O’Keeffe’s fluid paintings invite viewers into a world where form and color melt into one another with a quiet, organic grace. Her works, often inspired by nature, reveal the hidden fluidity of even the most solid forms. Whether depicting the curves of a flower or the undulating lines of a desert landscape, O’Keeffe masterfully uses soft, flowing shapes to evoke a sense of movement and transformation. Her brushstrokes are deliberate yet delicate, blurring the boundaries between object and atmosphere, making the familiar seem both intimate and infinite.

Sonya Derviz's work, much like Georgia O’Keeffe’s, delves into the fluidity of natural forms, yet Derviz expands this exploration into a more abstract, almost ethereal realm. Where O’Keeffe’s paintings evoke the gentle curves of flowers and landscapes, Derviz translates this organic fluidity into sweeping, amorphous compositions that seem to dissolve the boundaries between form and space. Derviz pushes these elements toward a more intangible interpretation of nature’s rhythms, where the fluidity becomes less about the object itself and more about the experience of movement and transformation. In her works, as in O’Keeffe’s, there is a delicate balance between strength and softness, between the familiar and the transcendent, with fluidity acting as a bridge between the visible world and the emotions it evokes.

Sonya Derviz's work also shares a deep resonance with Ana Mendieta's Silueta series, particularly in their mutual exploration of the human form's connection to nature. Mendieta's haunting sea silhouettes, where her body merges with the natural elements, evoke a powerful sense of dissolution—where identity becomes intertwined with the earth and water. Similarly, Derviz’s abstract, fluid compositions blur the distinctions between form and environment, embodying the idea of transformation and unity with nature. Both artists evoke a sense of impermanence and continuity, where the human presence is absorbed into the natural world.

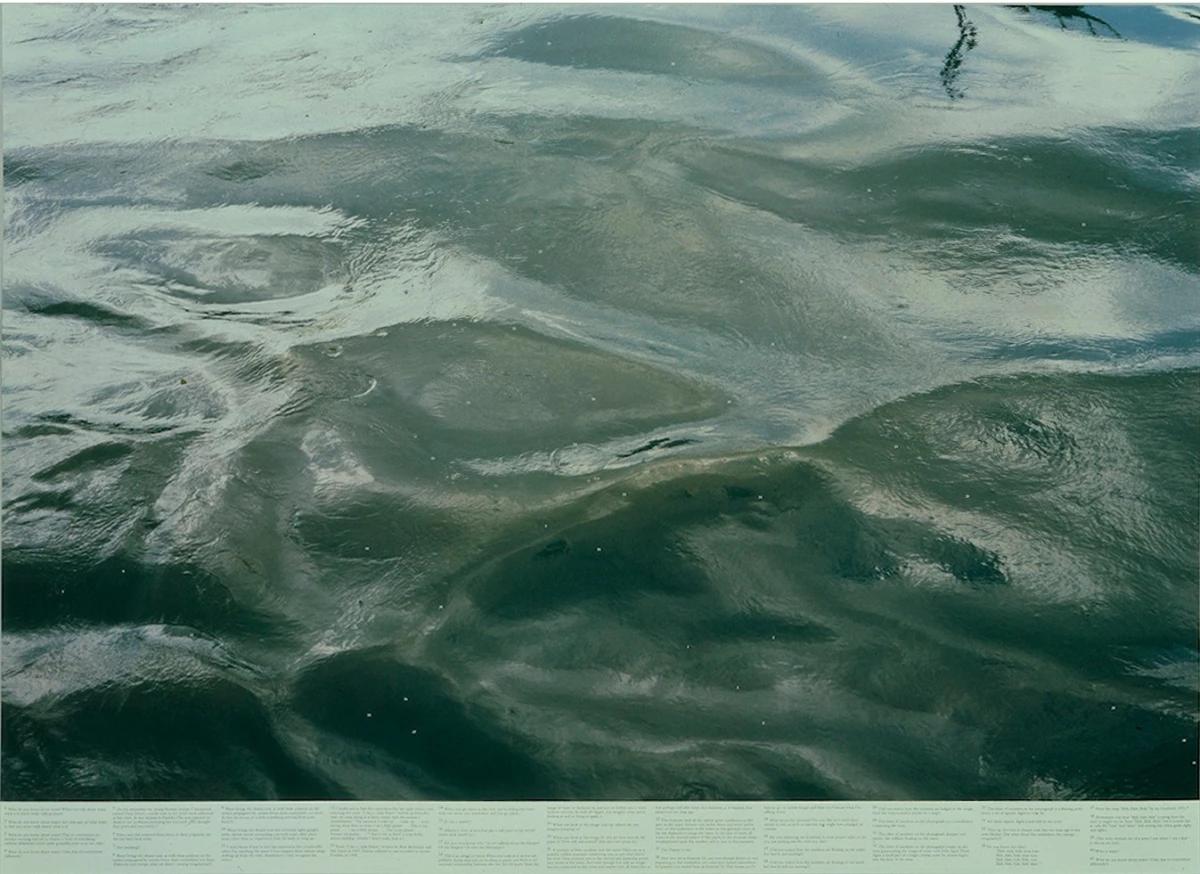

Fragments of narrative

Roni Horn's Still Water (The River Thames, for Example) explores the notion of fragmentation through its representation of the Thames as a series of photographic moments, each image capturing a fragment of the river’s fluid, ever-changing surface. In these works, Horn puzzles together disparate reflections and currents, emphasizing how water, though seemingly continuous, is always in flux and never truly whole. This fragmented portrayal of the river mirrors the way our perceptions of nature, time, and identity are never fully unified, but instead composed of fleeting, partial experiences. By annotating the photographs with personal and poetic reflections, Horn deepens the fragmentation, introducing another layer of interpretation and memory to the already fragmented subject. The river becomes not just a physical body of water but a metaphor for how we piece together meaning from fragmented, fluid moments in our lives.

Roni Horn’s Still Water series, where the Thames is captured in fragmented, fluid moments, finds a profound resonance in the recent work of young French artist Marilou Poncin, who paints intimate scenes within the hollows of seashells. Both artists engage with the powerful symbolism of water as it relates to life and death, using natural elements as metaphors for these fundamental cycles. In Poncin’s paintings, seashells—symbols of protection and birth—hold delicate moments of creation, gesturing toward the passage between life and death.

Water, both life-giving and destructive, is a central theme for both artists, embodying the capacity to hold memory and reflect the fragility of existence.

Water, both life-giving and destructive, is a central theme for both artists, embodying the capacity to hold memory and reflect the fragility of existence.